In a time of crisis, there’s an abundance of actions and words that, behind their good intentions, are likely to fail outright–or, even worse, come across as tone deaf.

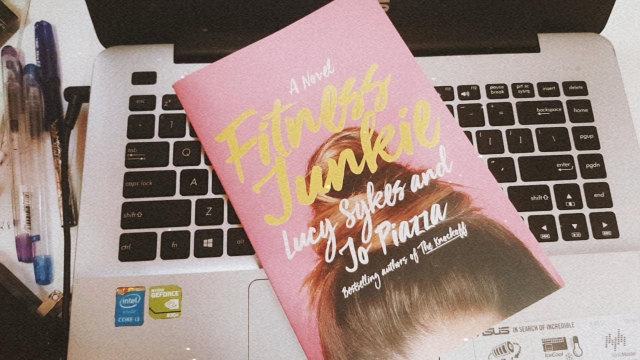

Reviewing Lucy Sykes and Jo Piazza’s Fitness Junkie might fall under the latter, if the intent is to review the novel as though removed from the period in which I finished reading it. It’s important, I think, to say that I finished it a couple weeks ago, rather than around the time I bought and started reading it. It’s been two years since, I think.

However, what’s strange–and what makes me want to write about this book today–is the underlying rigidity of having to stay fit while at home. Good health is a must more than ever today, sure. But I can’t quite reconcile this need with the way “fitness” has been co-opted in today’s discourse, in that the assumption seems to be that one must not, at any cost, gain weight during quarantine.

It’s an attractive way of thinking, largely owing to the micro-culture that one becomes bombarded with: a pseudo-lifestyle suddenly redundant with a variety of free yoga classes, HIIT routines, and other what-have-you exercise programs that you can do from the comfort of your home–assuming, of course, that you are at the very least bougie (or maybe even middle class) enough to have the space for keeping fit.

At this point, it’s probably best to say that I have nothing against staying fit at home. As someone who tends toward anxiety, one reminder I’ve clung to is that it is more fruitful and assuring to focus on the things I can control rather than the voluminous but vague idea of terror looming in the horizon. Following that sage advice, so far I’ve realized that some of the things I can control vary from the donations I can make, causes I can support, verifiable information I can help spread, the number of hours I [try to] sleep at night and yes, even the number of times I work out and how I choose to work out every week.

Having said that, I’ll be the first to agree that exercise does wonders for self-esteem. More importantly,exercise helps to introduce some structure to the looseness of my days. Following a ritual or two prevents me from being swallowed up by fear and ennui. Time once again begins to have some illusion of structure. And this is precisely why I do understand the steady if irrational desire to keep oneself distracted with a plethora of choices when it comes to staying active at home.

That’s not to deny that there’s nonetheless something cringe-worthy and authoritarian about the discourse of staying fit during quarantine. With every exercise program suddenly made free on fitness apps, with every Instagram story of someone exercising (or rejoicing after a workout, i.e., me), and with every online illustration of stuff one can do (read: accomplish, produce) during quarantine, the resulting idea is this:

That to lack a fitness regimen with a matching balanced diet is to fail at something fundamental. That to lack so-called discipline in a time of a global health crisis means that you’ve decided to “let yourself go.” That while good health is the heated campaign of the moment, you’ve somehow taken the less-traveled and completely erroneous path instead.

And yet…while it might be true that now more than ever one needs to take care of one’s health within the limited boundaries of home, I think what I find disturbing about the discourse of fitness, especially for women, is that it lacks re-imagination and the necessary adjustments that such re-imagining entails during a pandemic.

In short, it is a refusal of vulnerability. Today, ordinary employees (especially those on a contractual basis) worry about financial security in a way they’ve never had to worry before. Small to medium enterprises are suddenly grappling with new ways to manage their supply chain and deliver their goods at the level of frustration that even larger businesses are experiencing–except, of course, that the latter have better financial systems to support their having to pivot their business models during such a crisis.

I know. I digress.

But my point is this: it does not bode well for us to insist that we can build a fitness regimen from the ground up when the changes to our lives are monumental. Although focusing on what we can control can ground us into mindfulness, the obsession with the need to prove that we are, indeed, maintaining or losing weight not only implies that those who are less privileged and unable to do so are lazy, but also that our worth in isolation has to be determined by rigidity: and that henceforth, we rob ourselves of the opportunity to examine what we need on a day-to-day basis.

Does my current state of anxiety require a lazy Monday? Or would a Monday that closely resembles office life pre-quarantine be more assuring to me? Should I binge-watch the day away after my Tuesday Zoom meeting? Or would having a video date with family and friends after my meeting boost my morale instead? Should I exercise four times in a row this week to pump up my endorphins and then maybe just take it easy next week so that I can have more R&R?

I imagine that such questions would vary from person to person, and it is exactly such variety and re-imagining that is necessary if one is to understand that the striving toward fitness is not always the same as wellness. Today one might want to achieve a fitness goal by using a 15-pound weight for a deadlift. For the next five consecutive days, however, one might want to take multiple naps or eat ice cream for breakfast. Is there a line to be drawn here in terms of indulgence? Sure. But just as we’re careful not to over-indulge, we should be equally careful not to hate ourselves for not being able to transform our extraordinary circumstances into a robotic spectacle where control means self-punishment.

So where does the book review come in?

Here it is, in brief:

Fitness Junkie is an enjoyable work of satire. To me, an enjoyable satire is one that’s grounded on both observation and fact while managing to narrate both with colorful commentary that’s seeped in irony. A good work of satire is capable of showing what goes on in the day-to-day, sure; but it also manages to imply that there might be something ridiculous about such daily operations. In Sykes and Piazza’s work, Janey Sweet goes on a quest to a slimmer waist and a lower number on the scale in order to fulfill the ultimatum set for her by her business-partner-slash-boss: lost 20 pounds or lose her job at B, their couture wedding dress company which, of course, only has sizes leaning on the small side.

It doesn’t take too long for the reader to realize that of course, Janey will come to her senses. That of course, between reviving her dating life and going on New-Age inspired retreats, Janey will eventually realize that she isn’t into drinking bike-blender smoothies and losing herself in a sober rave after a long flight. That she wants someone more reliable and who has his shit together, rather than a guy who lives “dangerously” in their pursuit of a life that’s both zero-waste and high-octane to the point of exhaustion.

Most of all, it’s no surprise how Janey realizes that

“[she’s] never going to be a size 2, or even a 4 or a 6 again, and that was just fine with her. It was amazing how easily weight found its way back when you weren’t starving yourself or forcing your body to burn calories in cruel and unusual ways.”

Put this way, it might seem like Fitness Junkie is a good piece of satire, but not too good a novel–which is a fair evaluation of the work. It’s an enjoyable read, but it’s not exactly a mind-blowing narrative. Its value, however, comes from reminding readers that many of the things we learn about losing weight and staying “fit” are marketing campaigns. One of the funnier parts of the novel, for instance, unfolds when it is revealed that there’s a current media campaign to start endorsing kelp as the new kale, thus usurping the latter as the royal vegetable of a healthy lifestyle. The wellness industry’s affinity for a particular vegetable or diet might not be completely devoid of scientific data, sure; but the consistency of different kinds of diets that resurface every couple of years with slight variations on their strategy and target audience also means that the production and consumption of these “fit and healthy” lifestyles have a lot to do with fad culture.

So then, why read Fitness Junkie? Janey’s redemption arc is predictable, after all, while the nature of satire assures the reader that clay-based diets and intense, name-calling workouts won’t get the last word in the narrative anyway. In this sense, however, it’s less the way the novel is written which matters. It’s more important, I think, to ask ourselves why such novels continue being written and consumed–because if there is still a need to satirize the way we look at and operationalize things like “fitness” and “wellness” especially when there’s a pandemic, then we have not yet, in fact, outgrown the tendency of falling for fads-as-truths–falsities to which we subject our bodies for the promise of some superficial acceptance.

Today, that “acceptance” takes the form of what I’ve already discussed above: the gold-star approval that you are indeed making the “most” of your time in quarantine and translating all your anxiety into pushups–3 sets with 20 reps each set, with 15 goblet squats between each set–over and over, every single day, without paying attention to the rest of your body, without taking into consideration, perhaps, that your mind remains on overdrive because you have prevented it from truly articulating and going through the actual fears that haunt you.

Exercise is good, yes. But our bodies and minds are multi-faceted structures that won’t always need the same thing again and again, over an uncertain length of time. Routine can be therapeutic, but without compassion, it is not discipline but cruelty.

It’s no wonder, therefore, that those who are most critical of their own bodies, diet, and workout regimen during this time–those who tsk at minimum wage earners who line up at wet markets; those who have forgotten that the homeless exist; those who advocate charity as the highest virtue–that it is these people who probably display a greater tendency to believe that the poor have determined their own fates and made the choice to become ill.